The thrill of smuggling creative contraband back into your routine

On the thrill of smuggling creative contraband back into your routine

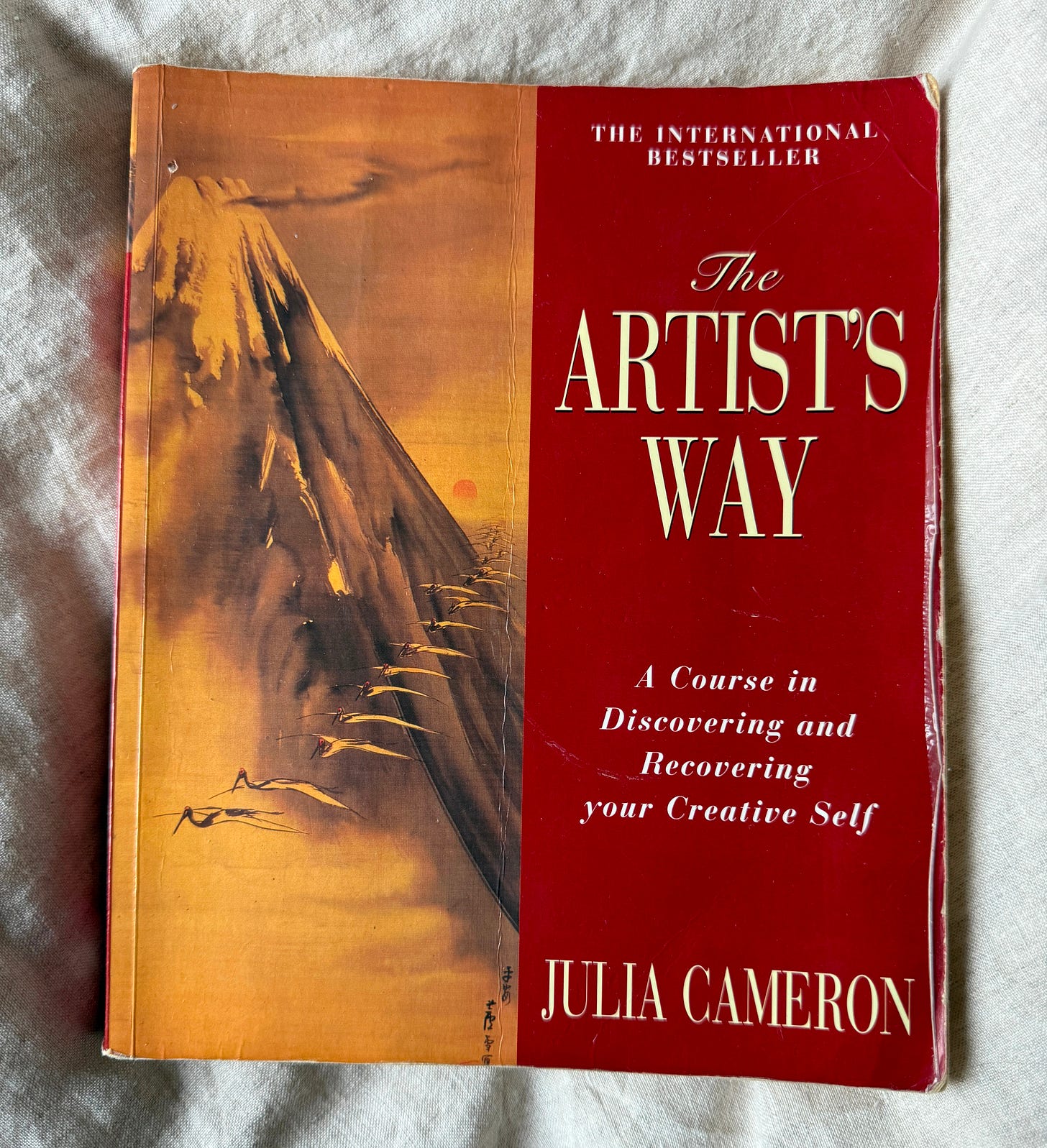

A few weeks ago, alone in the house for the first time in months, I went up to the loft. I can’t remember what I’d gone up there for, but what I carried back down was a book: my old, battered copy of The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron.

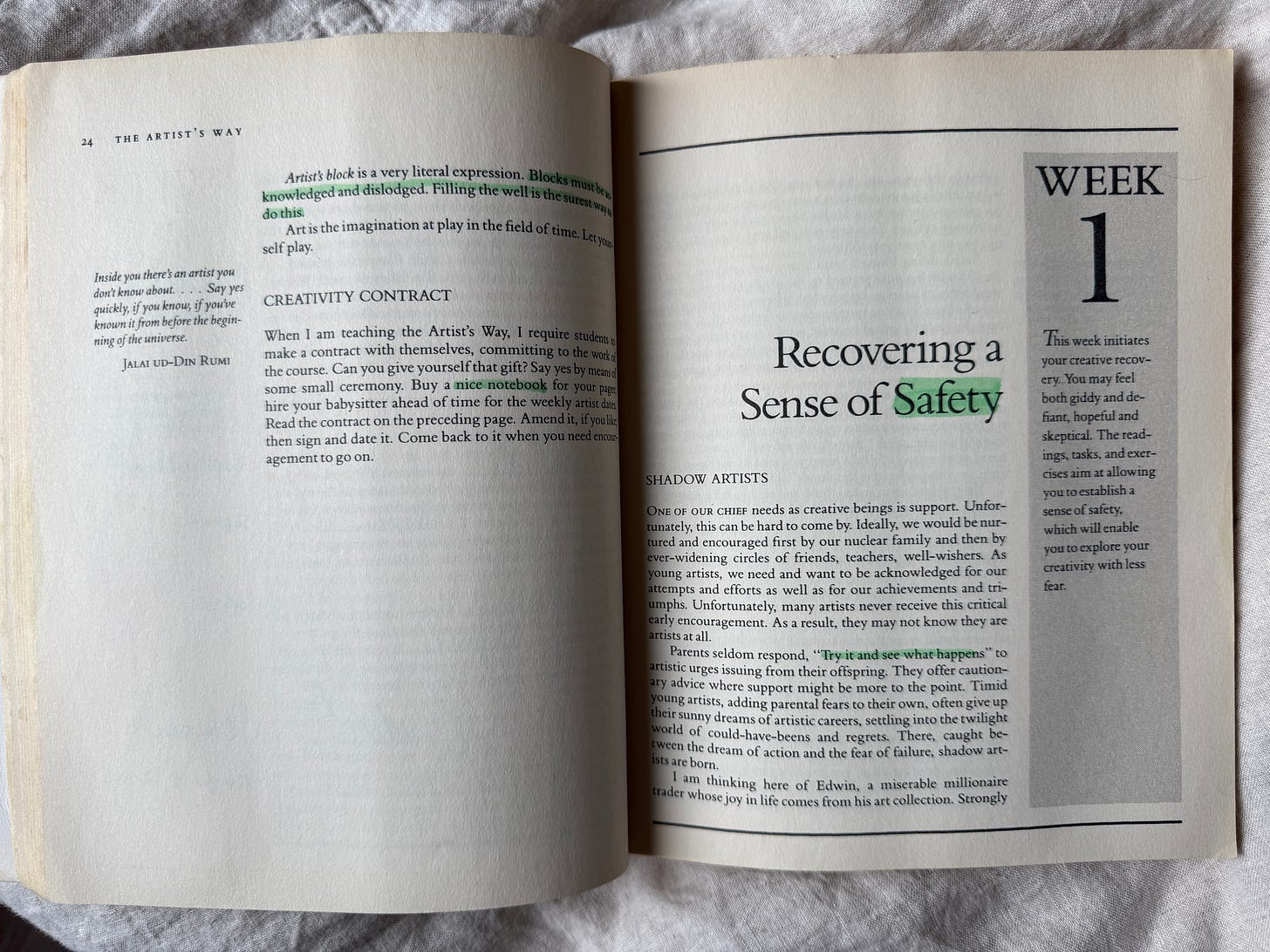

The spine was cracked, the cover sun-faded, its pages scattered with my younger self’s hopeful underlinings. Certain sentences were still glowing with fluorescent yellow, though the ink had long since dulled. In the margins, notes in a handwriting that didn’t quite feel like mine anymore.

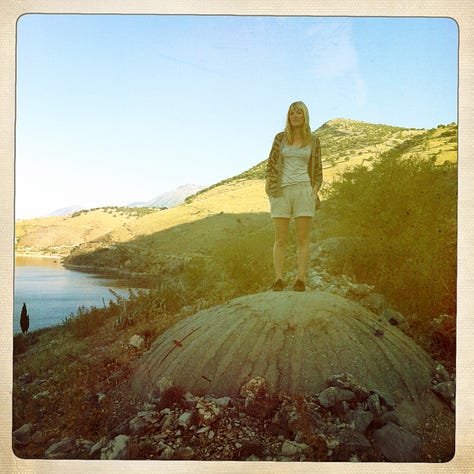

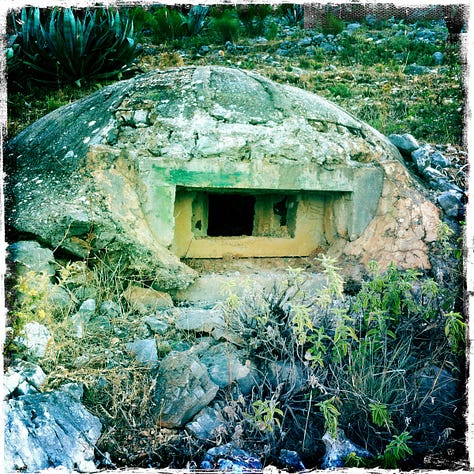

On page 23, in neat biro, was a pledge — signed by me in July 2013 — more than a decade ago. Seeing that date was like opening a time capsule I hadn’t meant to bury. I’d been in my twenties, on holiday in Albania. My partner and I had chosen somewhere cheap and disarmingly remote, with no car and no plan beyond the aquamarine bay below. The hills were scattered with eerie Cold War bunkers — hulks of concrete half-swallowed by wildflowers.

One afternoon we hiked into the scrubland and found the papery ghost of a snakeskin. In that strange place, I opened The Artist’s Way for the first time, as if trying to shed a skin of my own.

Julia Cameron and her radical permission slip

First published in 1992, The Artist’s Way is part self-help manual, part spiritual text, part creative bootcamp. Julia Cameron — American writer, filmmaker, teacher, often called “the godmother of creativity” — designed it as a twelve-week course to “recover your creative self”.

Its two central practices have become near-mythical: Morning Pages (three longhand pages of stream-of-consciousness writing every day) and the Artist’s Date (a weekly solo adventure with your creative inner child).

The book has sold millions, translated into dozens of languages, passed hand to hand like contraband, whispered about by artists, writers, and anyone secretly longing to make something. Some swear by it, and some, I’ve discovered (an author I met at Gladstone’s recently) hates the very concept!

But at its heart, Cameron’s method is about permission. Permission to take yourself seriously as a creative being. Permission to write badly, to waste time, to play. Permission to say no to what drains you, and yes to what sustains you. No wonder it feels forbidden.

Our culture rarely encourages adults to be frivolous or experimental. But Cameron insists that creative play isn’t indulgence — it’s oxygen.

The woman I was then

Looking back, I hardly recognise the woman who signed that pledge in 2013.

The year before, I’d moved from Leeds to London, which promised so much more. I’d clawed my way into a position at The Sunday Times — barely more than glorified work experience. Until the move, I’d been commuting south, crashing on friends’ floors, trying to stand out in a newsroom that thrummed with competitiveness and toxicity.

When my broadsheet colleagues asked about my parents or my schooling, I froze. I carried so much shame, like I wasn’t enough to even exist in those rooms. I felt perpetually exhausted, brittle, unformed.

Back then, I hadn’t yet become the person I now recognise. I hadn’t started running — that came later, after I tentatively downloaded Couch to 5K age 30. I hadn’t discovered mudlarking — a passion unearthed in lockdown, one that grounded me in history and mystery. Most of all, I hadn’t written a novel. The very thought felt impossible, reserved for other people.

And yet, without realising it, I was sowing seeds. Scribbling those Morning Pages, taking myself on hesitant Artist’s Dates — I was training my mind to believe that I could be a writer.

A decade later, I can trace a line — faint but visible — from that July in Albania to the books I eventually published: The Flames, about the muses of Egon Schiele, and Madame Matisse, about the women who shaped Henri Matisse.

Both novels sprang from the same root: a desire to reclaim female voices erased from art history. If I hadn’t opened The Artist’s Way then, I wonder whether I would ever have dared.

Returning now

So why return to it now, in 2025? Is it going to change my life again…?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Forbidden Art to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.